The Temple Mount in Judaism is said to be the place

where God gathered dust to create Adam, the place where Abraham bound Isaac for

sacrifice, the location of the first and Second Jewish temples, and the home of

the Foundation Stone from which the Earth itself was created.

The Haram al-Sharif, or Noble Sanctuary, is the third holiest site in Islam. It holds the Al-Aqsa Mosque, to which Muhammed made a miraculous journey from Mecca in only one night. For a time, in the early days of Islam, Muslims were instructed to pray towards Jerusalem instead of Mecca, and the site of the glittering Dome of the Rock is where Muhammed is said to have ascended to heaven.

Unfortunately, these two sites are the exact same

place. The Mount sits directly above the blocks of the Western Wall, the remaining piece of the Jewish temple. After the

site was conquered in 1967 by Israel, it was immediately turned over to

Jordanian control to avoid inciting a war, and it remains in their control

today. It is one of the most politically and religiously charged places in the

world, and is a pin in the semi-dormant grenade of the Israeli-Palestinian

peace talks.

The ascent to the Mount is not made easy by any means.

Non-Muslim visitors are only allowed to ascend between 7 and 10 in the morning

and between 12:30 and 1:30 in the afternoon, so that they are only there in

between prayer times. Non-Muslims are also not allowed into the Dome of the

Rock or the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Islam maintains a very private, mysterious, and

exclusive air in a city where religions are so jumbled.

Visits require strict security as the site often erupts into sometimes violent

political displays and protests. Non-Islamic prayer is not allowed on top, so

bags are searched to remove any books written in Hebrew that might be used for

prayer.

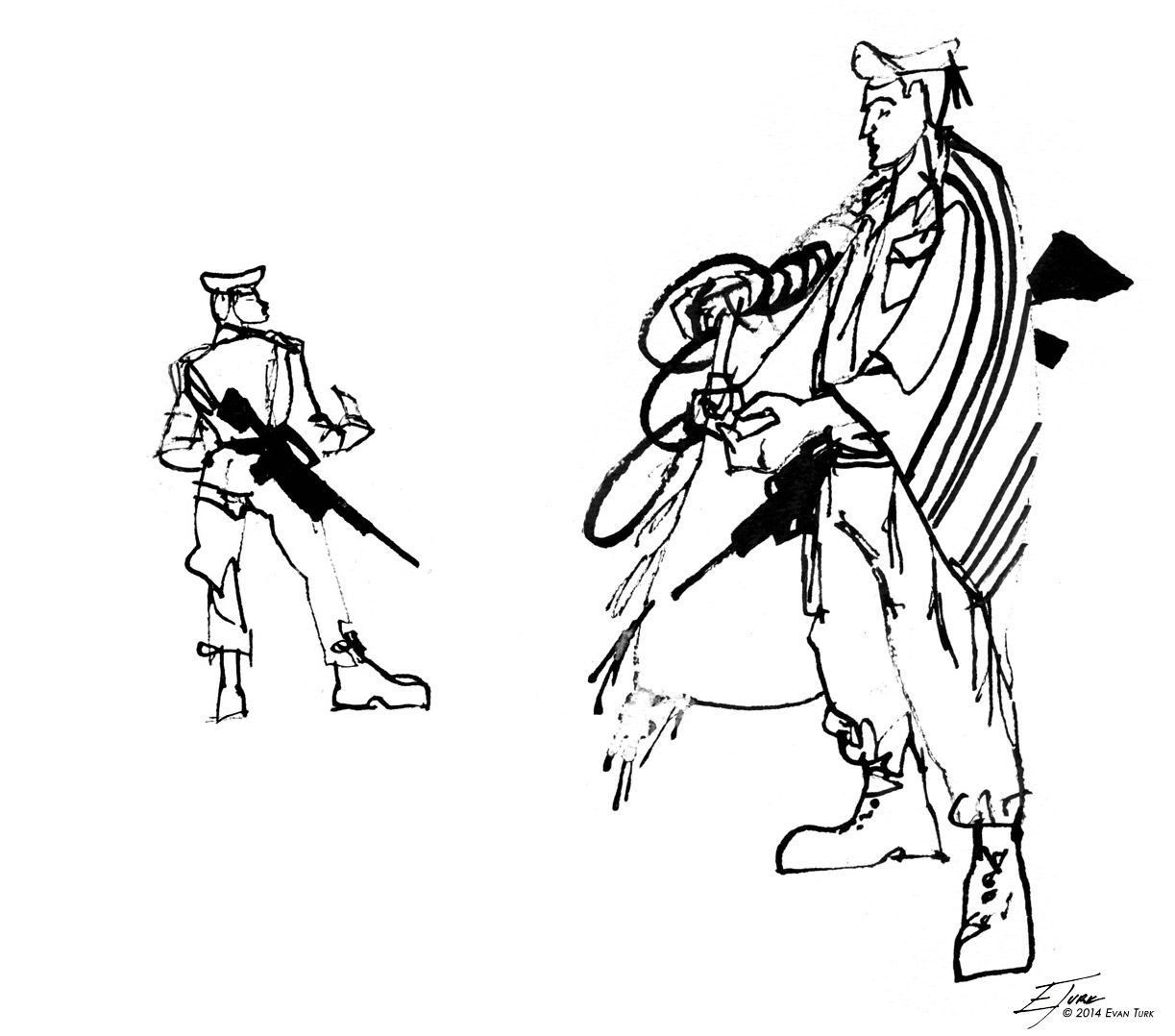

Once the gates were opened, I climbed up a narrow, rickety

plank to the top of the Mount where beaming sun, the gentle murmur of

conversation, and several Israeli guards with machine guns welcomed me to the

most beautiful place in Jerusalem. The expansive terrace is covered with gnarled old Cyprus trees, palm trees, glittering

fountains, and students of Islam in quiet circles reading and studying the

Qur’an under the twinkling shade.

Behind the gardens looms the impressive, glittering gold of

the Dome of the Rock. After ascending a staircase and passing under a delicate

archway, I emerged onto a stark, desert-like plateau. In the center, the

Dome of the Rock stood like a fortress, immovable and imposing. Tiny, ant-like

people moved around the base of the structure, dwarfed by its weight and

austerity.

Its surface pulsed with intricate tilework and windswept Arabic calligraphy. Cursing my blonde hair, pale whiteness, and obvious not-Muslim-ness, I watched as men and women in long flowing robes passed in and out of the doors, freely able to see the beauty of the interior.

Its surface pulsed with intricate tilework and windswept Arabic calligraphy. Cursing my blonde hair, pale whiteness, and obvious not-Muslim-ness, I watched as men and women in long flowing robes passed in and out of the doors, freely able to see the beauty of the interior.

As my very short time on the Mount dwindled, I went back down to the

Al-Aqsa gardens to draw the men and women milling about and reading from the

Qur’an. In contrast to the emptiness of the area surrounding the Dome of the Rock,

Al-Aqsa plaza felt very much like a college campus, with students (of all ages)

passing to and fro, books tucked under their arms, reading and studying

together in large circles, separated by gender.

Suddenly, the solemn quiet erupted into a howling chant that

began in the distance and slowly began to move from circle to circle, like the

wave at a baseball game. “ALLAHU AKBAR!” each group would shout in turn, until

the entire plaza, and hundreds of people were all shouting with increased

fervor. I continued drawing, not sure what was happening, until I asked a

nearby man.

He told me that people were shouting because extremist Jews had entered the Haram al-Sharif with an armed Israeli escort. He said these Jews sought to destroy the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque to rebuild the Jewish Temple. It is true that an extreme, right wing Jewish faction is gaining traction in Israeli politics, and part of their platform is the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount. The shouting would start intermittently every 20 minutes or so, and last for several minutes as the Jews and their guard moved through the plaza.

As I was drawing the angry crowds shouting at the two men walking through, I became nervous that the onlookers might be offended by my depiction of them. On the contrary, it energized and excited them. Men began calling their friends over to point out people they knew in the drawing, and seemed very pleased that I had accurately depicted their anger. They seemed to feel validated by my drawing. I wonder if the Jews I drew in the picture would have felt the same way, and been equally validated in their reading of the drawing.

The Mount itself has become an illustration of whatever anger or righteousness each side of the divide feels entitled to. Within it are the seeds of Israel and Palestine’s most festering wounds and also the potential for its most poignant healing. Its contested nature is a testament to the deep, shared roots of Islam and Judaism: two seeds of the same fruit.

For

more of Evan Turk's travel illustration, check out the link below: