The Western Wall, or kotel, in Jerusalem is considered the most

sacred place in Judaism, and has been a pilgrimage site for Jews since the 4th

century. A wall of enormous blocks of Jerusalem limestone is all that remains

of the Jewish temple built by King Herod in 516 BC, after its destruction by

the Romans in 70 AD. When writing about holy Jewish and Muslim sites in

Jerusalem, every sentence is a political statement. Even the previous sentence

is loaded, since some Muslims believe that Judaism has no religious claims to

anywhere in Jerusalem. When discussing the area around the Wall, it becomes

even more difficult. Under Jordanian rule, from 1948 – 1967, Jews were

forbidden to come to the wall. When Israel conquered Jerusalem in 1967,

they liberated the wall for Jews in an emotional celebration, and demolished

the Muslim neighborhoods that surrounded it in the now non-existent Moroccan

Quarter.

Politics aside, there is no denying that the Western

Wall is an incredible pilgrimage site for millions of Jews around the world.

This pile of stones, with no special aesthetic value above any of the other

stone walls around the ancient city, is made sacred only through the prayers

and connections of the millions of pilgrims that place their hands against its

cool, hand-worn surface.

In contrast to the solemnity and darkness of the

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the outdoor Wall Plaza is often full of singing

and celebration. Bar mitzvahs, celebrations for boys entering manhood at age

13, are held in front of the wall every Monday and Thursday.

Boys beam from ear to ear as they carry enormous Torah scrolls with the men of their family.

After the ceremony is complete, the congregations erupt into swirling circles of dancing and singing of the hora, as female relatives and onlookers peer over the divider between the men’s and women’s sides of the wall and toss candy as tradition.

Another Jewish tradition, tefillin, which consists of small black boxes containing verses from the Torah, and leather straps wrapped around the head, arm, hand, and fingers, is worn by observant Jews during weekday morning prayers. The origins of tefillin in the Torah are fairly vague in their symbolism, but they are described as a reminder of God’s bringing the Israelites out of Egypt and a protection against evil thoughts.

There is a stall near the plaza that will wrap the tefillin for you, to experience the prayer. The man asked if I would like to try it, and I asked what the meaning behind it was. He described the leather strap, which runs from the parchment scroll box, around the arm tightly down to between the fingers, serves as a symbol of connection between mind, heart, and hand. It is a physical reminder that a person should strive to connect his thoughts and feelings into action.

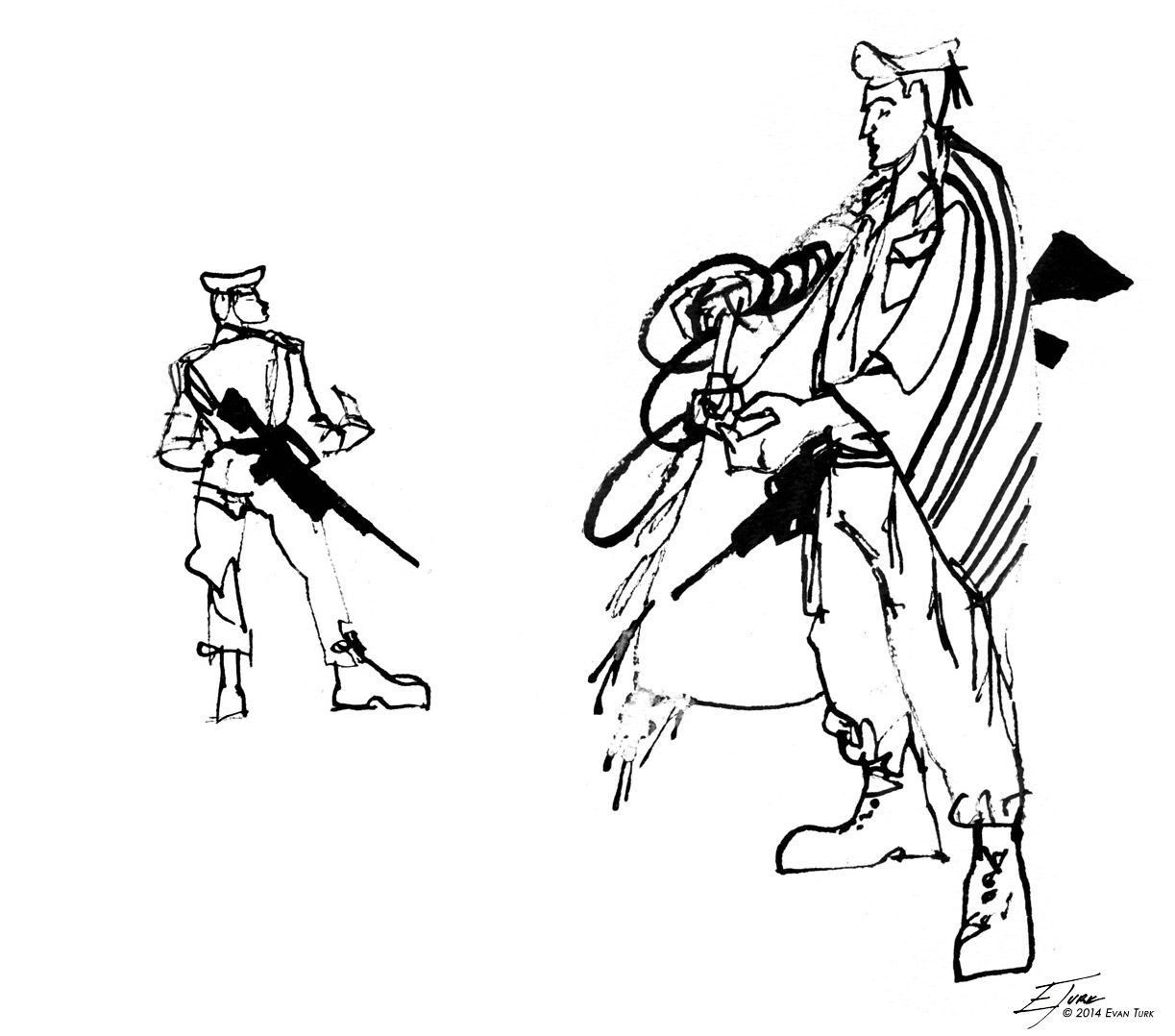

I saw a group of soldiers from the Israeli Army have the tefillin tied and the talit, prayer shawl, draped around their shoulders. They all then prayed at the wall, and several of them also wrote notes and put them in between the cracks of the stones.

Most of the moments at the Wall, though, are of quiet,

personal connection. Young men and old men alike place their hands and heads

against the Wall in quiet prayer. Proud fathers lead their sons to touch the wall for

the first time.

Men often leaned against the Wall for so long, eyes closed, sometimes with tears falling down their cheeks, that when they opened their eyes, the sun was too bright and they looked like they had awakened from a trance.

The cracks between the stones burst with prayers and wishes written on scraps of paper and pushed as close to holiness

as possible.

It is these spaces in between the stones that are

sacred, physical reminders of hope. Like the plants that grow from in between the stones,

there is the potential for life.

The Wall stands, not as a monument to a temple that existed two thousand years ago, but as a monument to tradition, hope, and connection.

For

more of Evan Turk's travel illustration, check out the link below: