I've been busily working on preparing for the release of my new book The Storyteller and have been neglecting my blog! But there are many new posts on The Storyteller website to read about the creation of the book and its art, as well as reviews, event announcements, and educational materials as the release gets closer (June 28!)

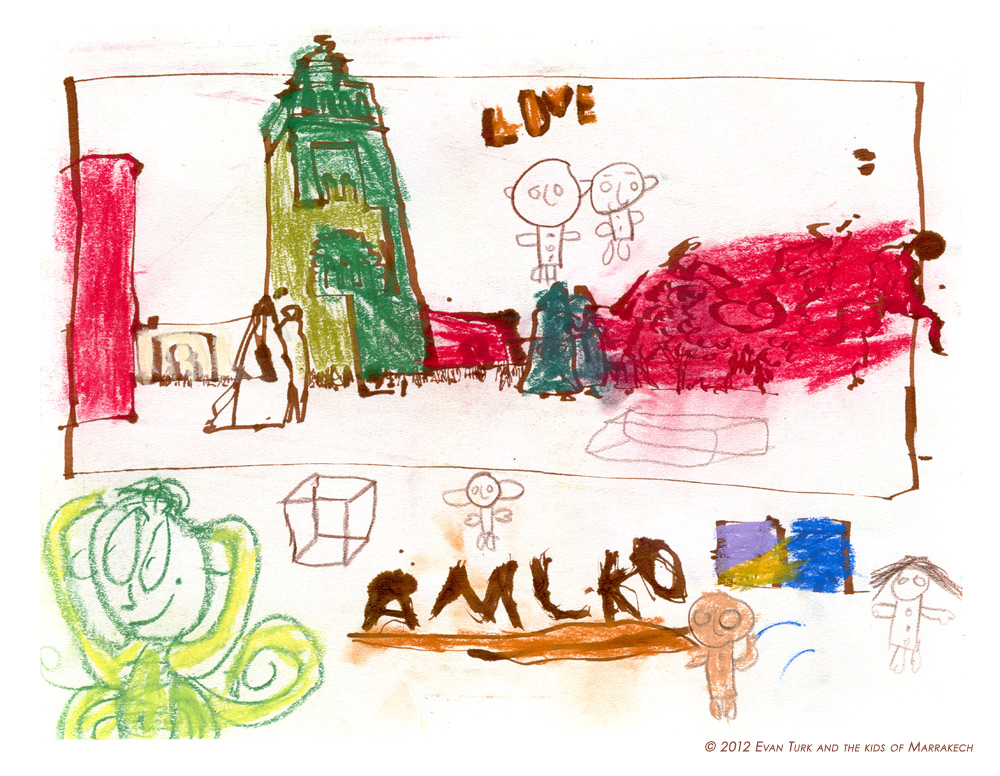

I am also very excited to announce that original artwork from The Storyteller, as well as some of these reportage drawings from Morocco and preparatory sketches, can be seen at the Brooklyn Public Library as a part of author/illustrator Pat Cummings' show "The Turn of the Page". Pat was one of my favorite teachers at Parsons, and is having a well-deserved residency at the Library. She has invited some of her former students who work in children's books to exhibit with her, and I am so honored to be included! I hope you'll come by and check it out! Opening reception the evening of May 9.

The post below is from The Storyteller website and features drawings from a research trip I took for the book in the fall of 2014.

---

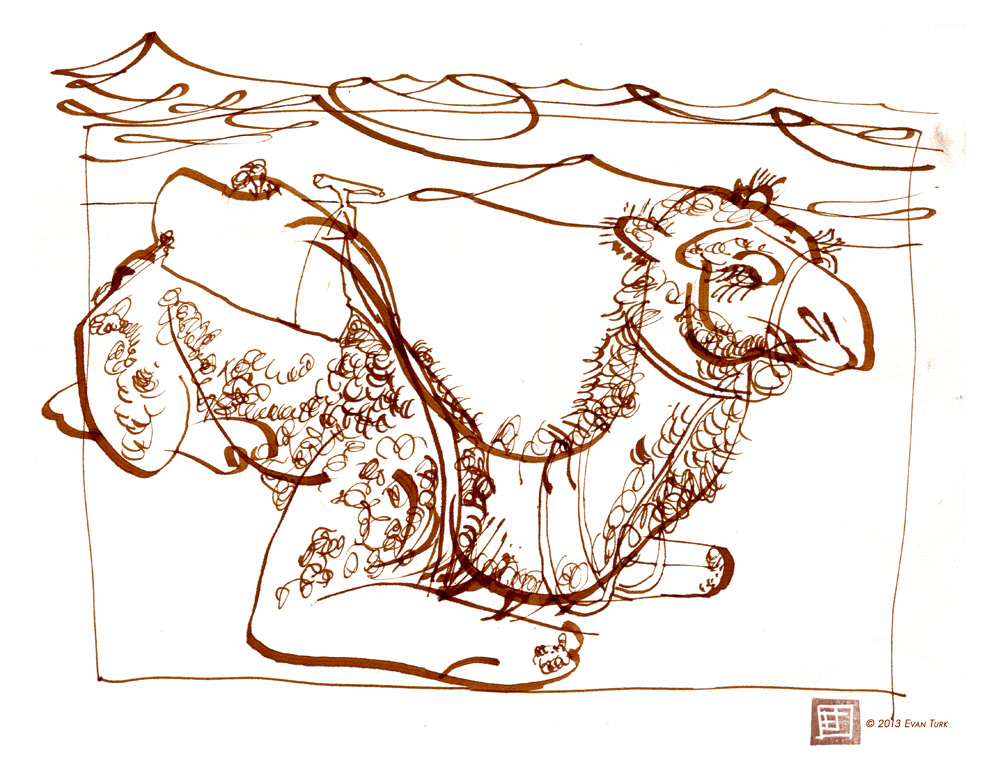

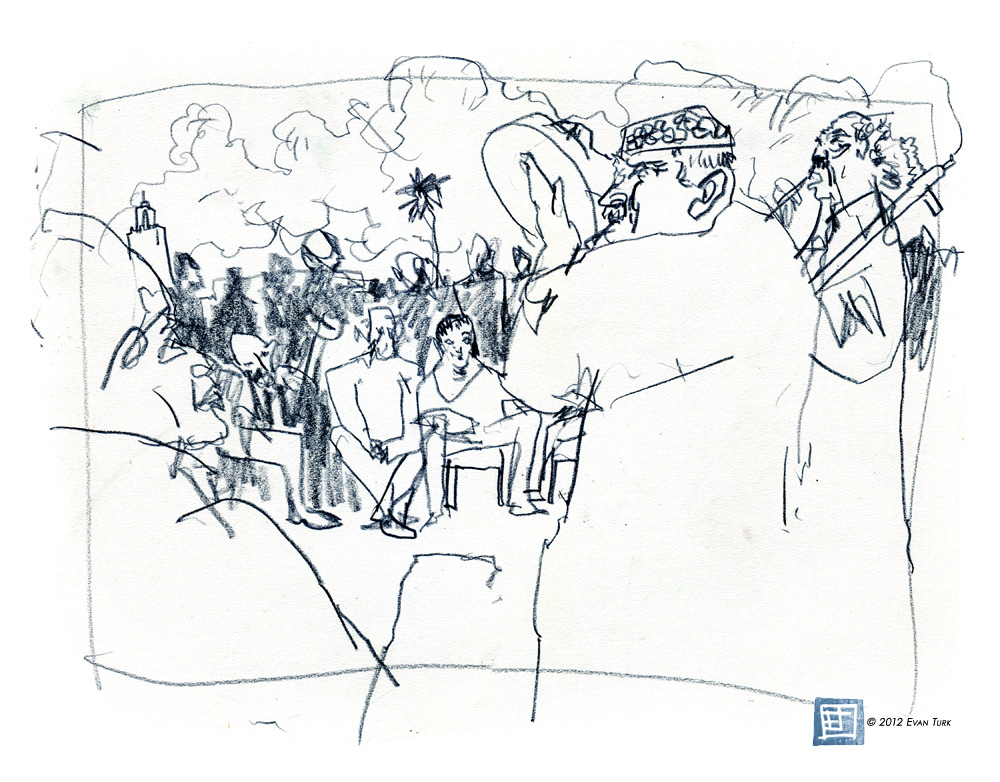

In October 2014 I took a trip to Morocco to do research for The Storyteller.

One of my favorite experiences was spending a day in the village of

Anzal in southern Morocco and meeting the women carpet weavers there and

their family. These drawings (aside from the illustrations from the

book at the end) were done on-location in Anzal and the nearby Oasis de

Fint.

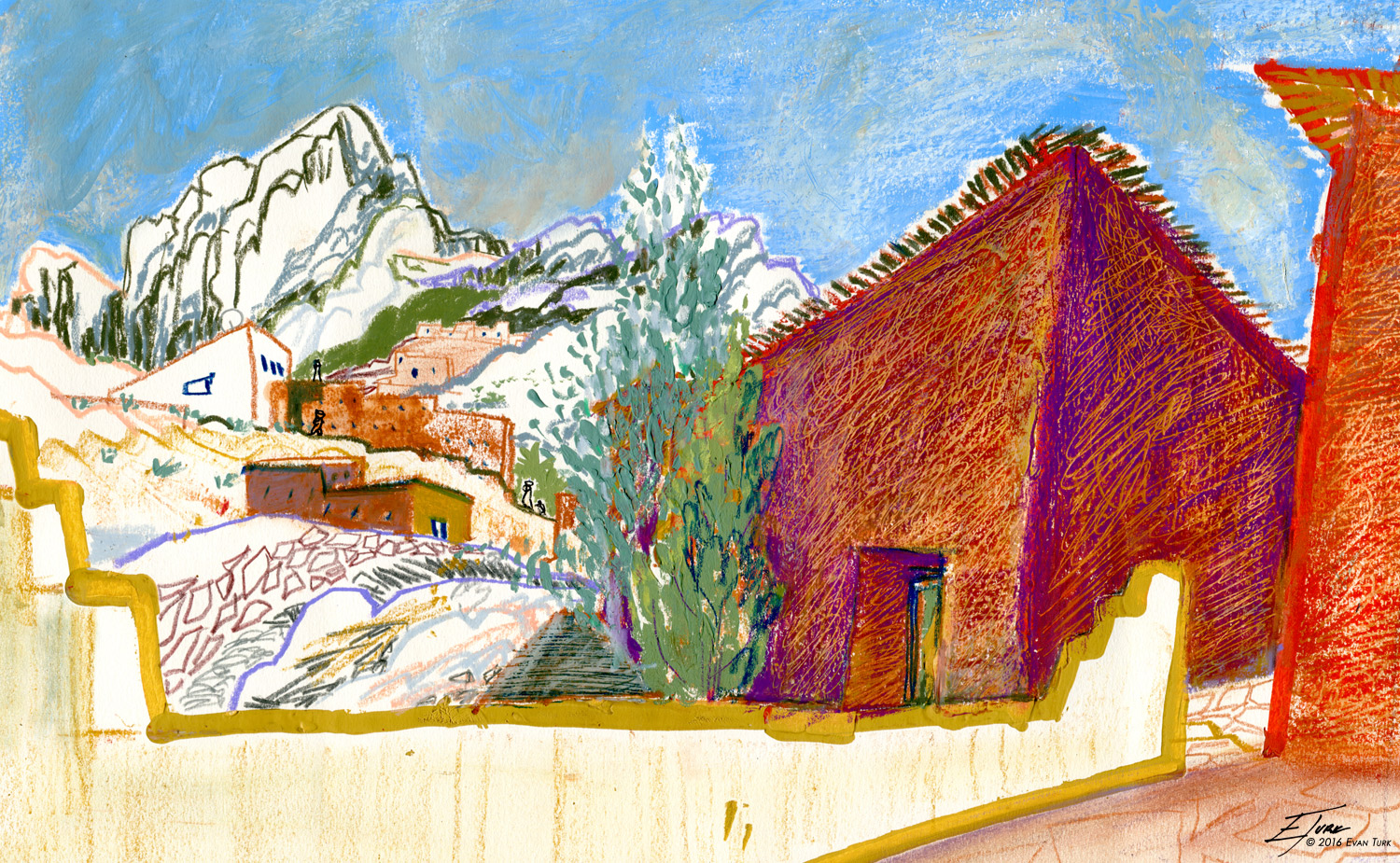

I

arrived at the village of Anzal and met, Naoual, a twenty two year old

woman from the village who translated for me and told me about her

village and the weaving association. The village is nestled in a valley

between harsh, dry mountains. The landscape is both empty and calming.

The ground and sky seem to extend in all directions for eternity. It is

said that the top crossbar of a loom is often called “the beam of

heaven” and the bottom bar, “the earth”, with everything between as

“creation.”

Naoual

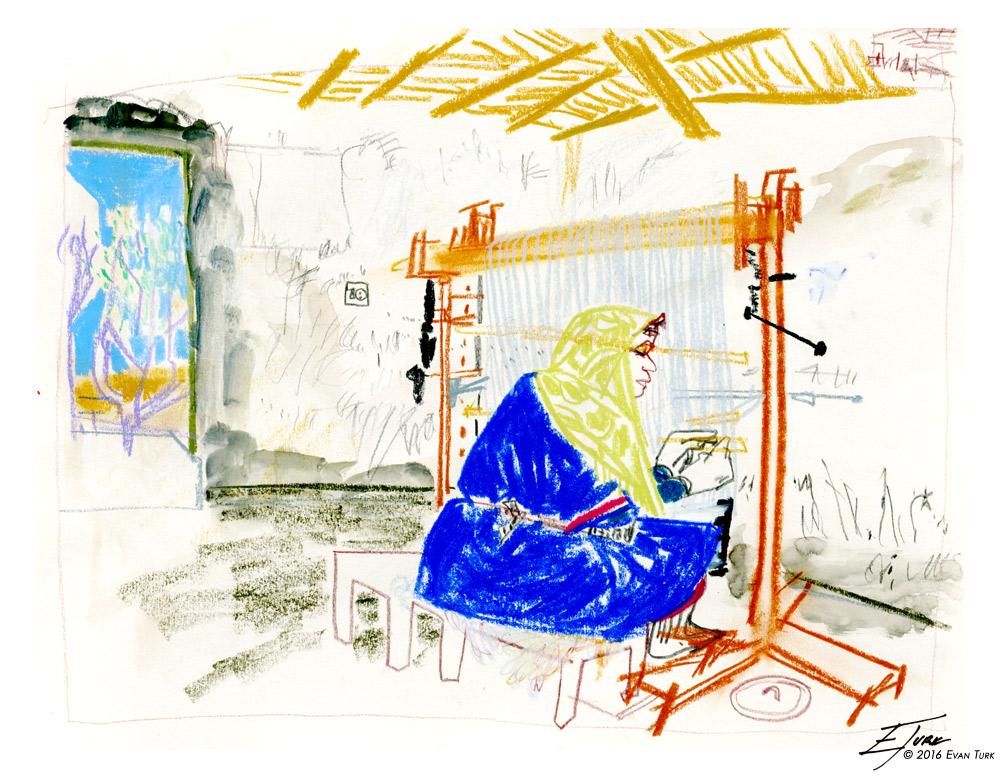

led me the short distance to the Association where I met Aicha, Fatima,

and Rahma, Naoual’s mother-in-law. Aicha and Rahma were seated in front

of their looms, made out of red steel I-beams and heavy wooden

crossbars. A net of vertical yarns, the warp, stretched between the two

crossbars in front of each weaver. Beside them were bags and cans of

brightly colored, short pieces of yarn that would be knotted

individually around each of the warp threads into a colorful design, the

weft.

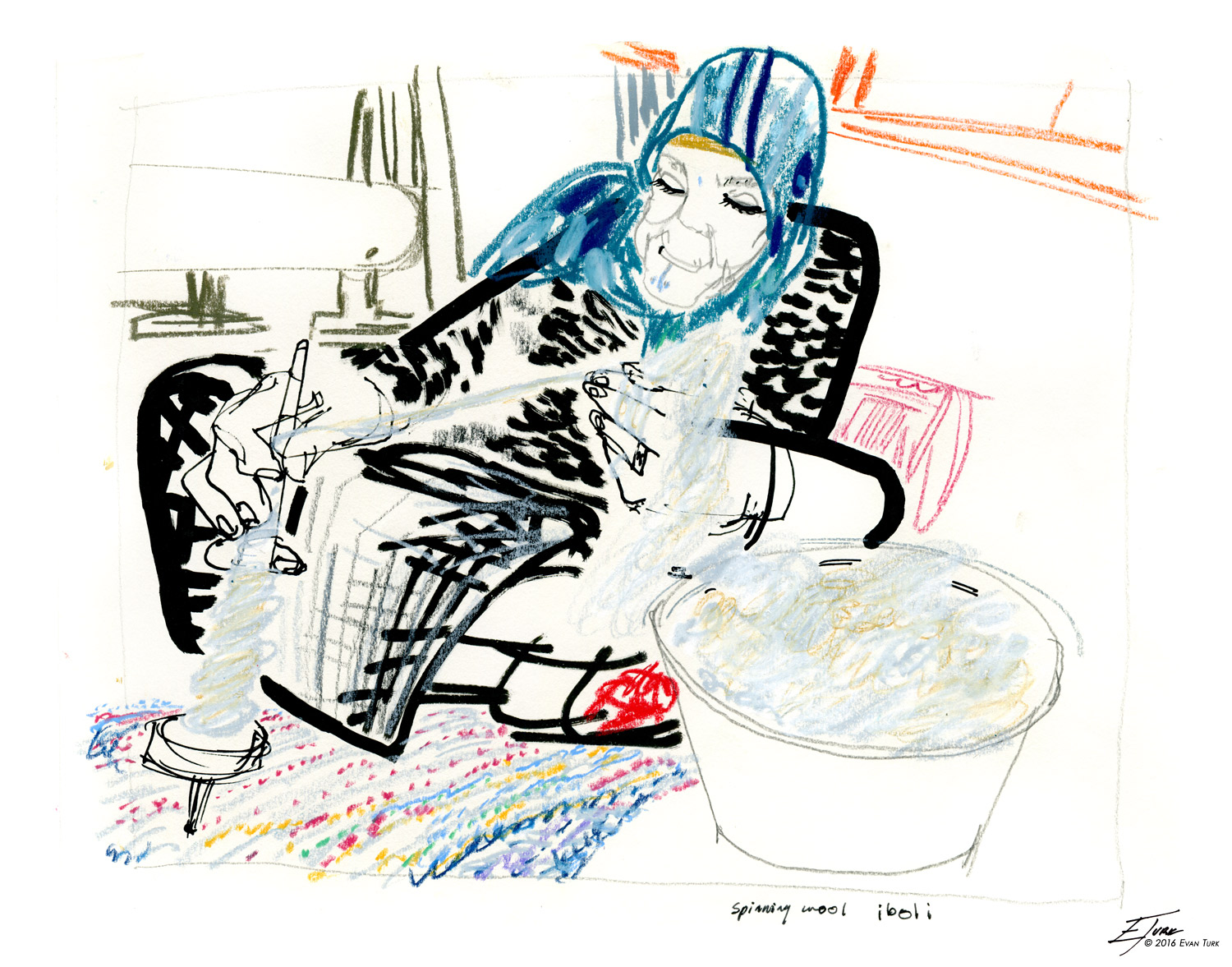

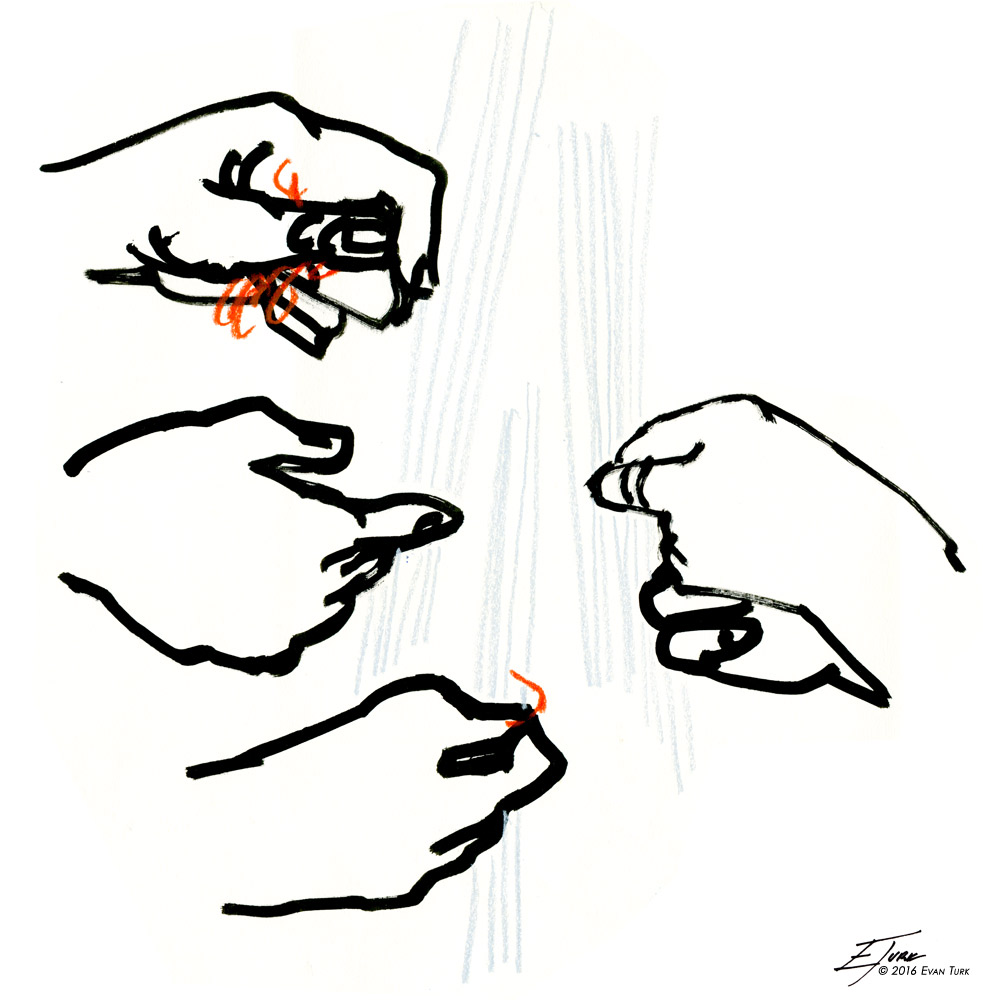

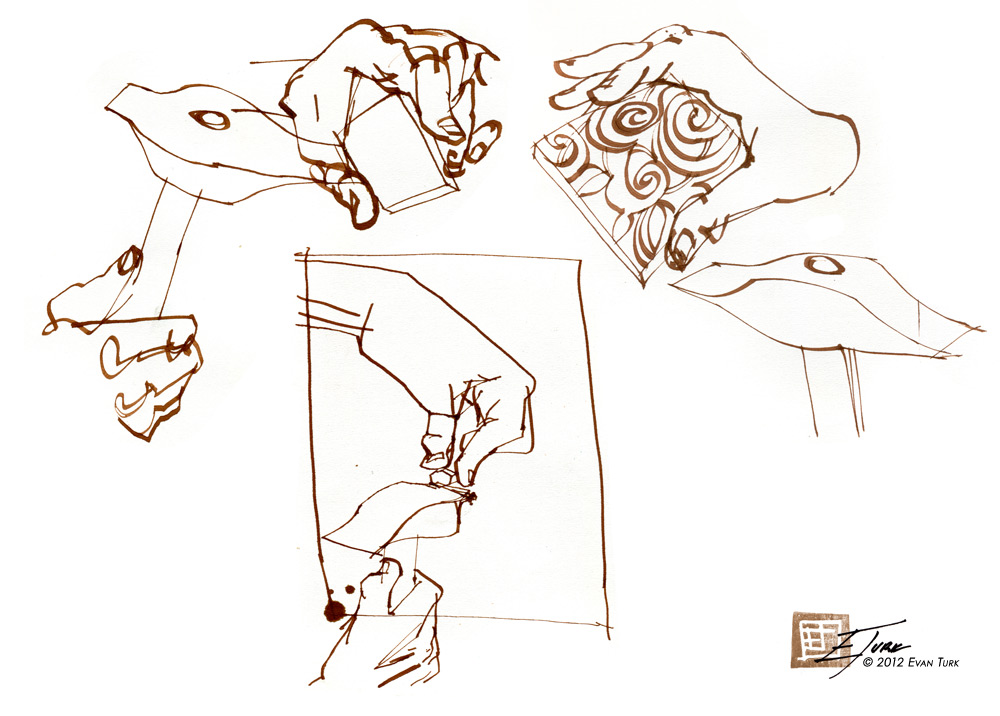

Fatima sat nearby Aicha, taking tufts of wool and winding them into yarn on a spindle, whirring between her fingers.

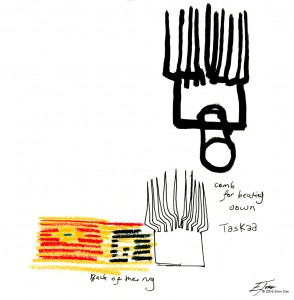

Aicha’s hands worked quickly, knotting each row, and then smacking the knots down with a comb called a taskaa, which resembled a big spider.

Spiders

are often associated with weavers, and their magical creative ability

in forming webs. The act of weaving feels both magical and utilitarian.

When you see a finished carpet, the staggering amount of work is both

hidden behind the beauty, but also evident in each individual knot.

Patterns

spread across the warp, slowly appearing as the weaver moves from side

to side, row to row. Symbols, triangles, diamonds, zig-zags, and other

shapes emerge. The symbols are infused with historic meaning, but also

with the individual whims of the weavers.

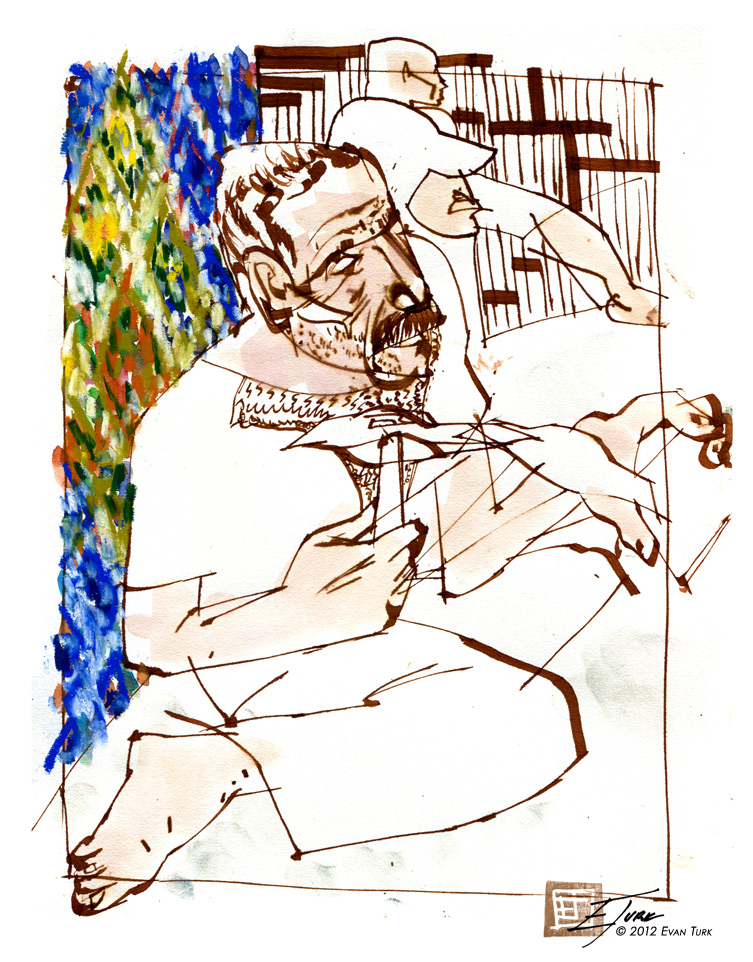

I

watched as Rahma struggled in contemplation in the early stages of her

weaving, trying to decide on a color and a direction. The dreaded “blank

page syndrome” that plagues all artists at some point, manifests in the

even more daunting “blank loom” which will be the home for her hands

for the next many hours and days.

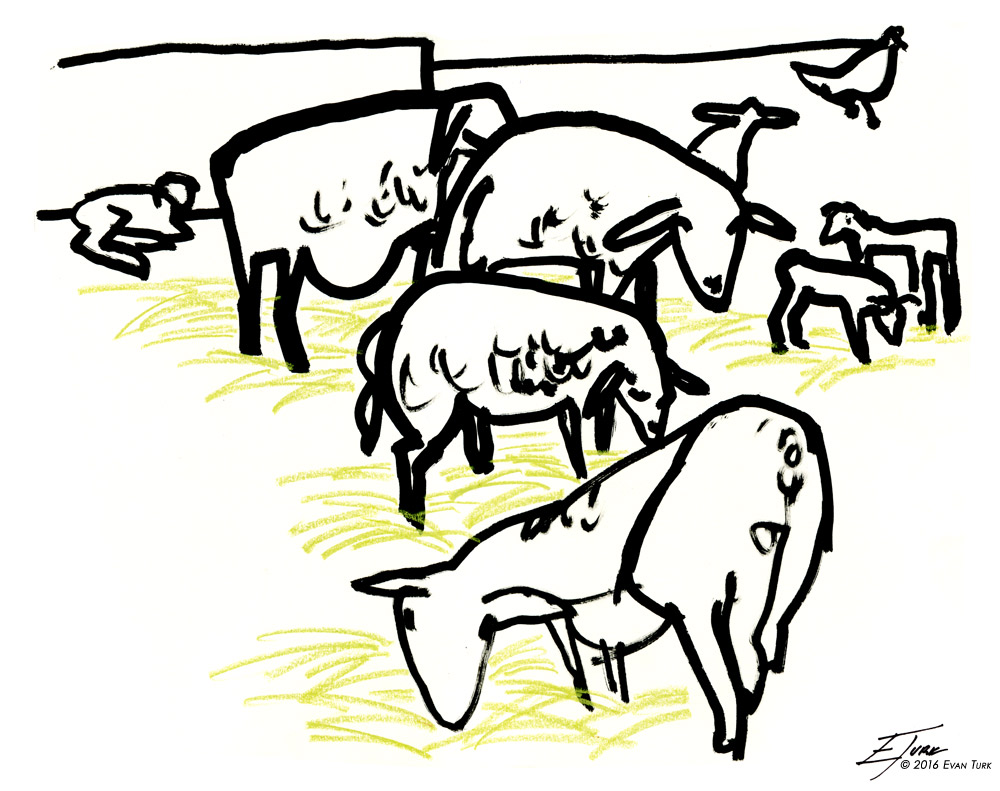

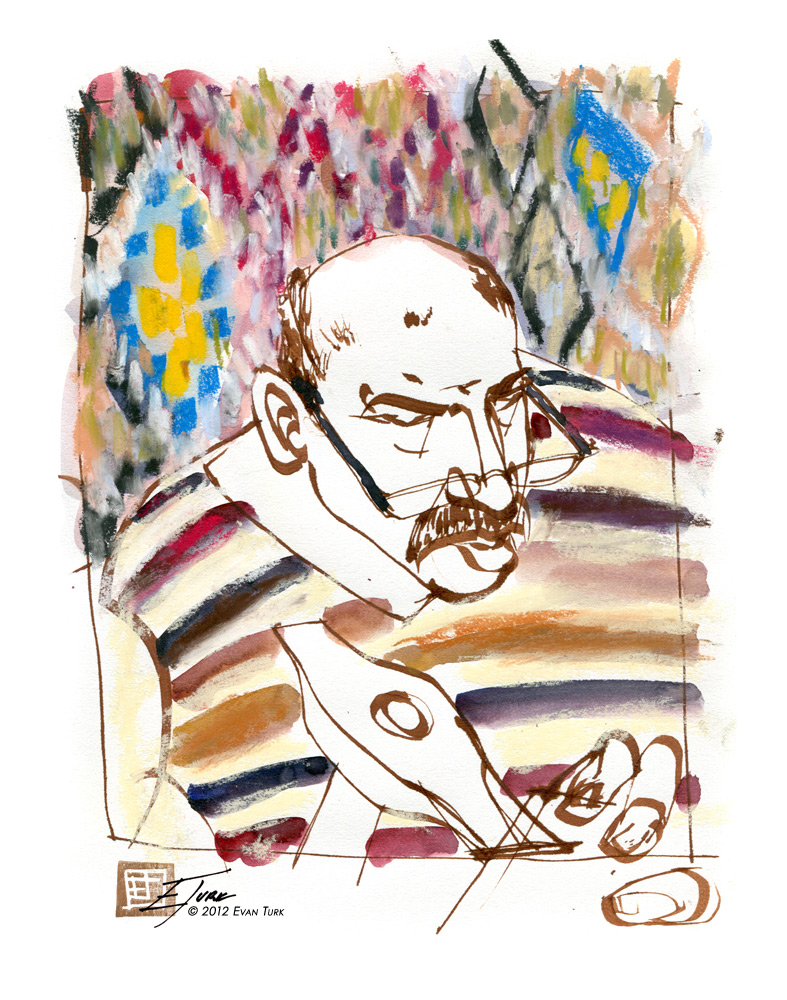

Naoual

showed me her family's sheep pen (who's wool is taken for the carpets),

and led me to her own house for tea and lunch with her mother-in-law,

Rahma, and Fatima, the spinner. I listened as they all spoke back in

forth in Tamazigh, as Naoual tried to keep me up to speed on the

conversation. We discussed the growing presence of Tamazigh people in

the national conversation, as it became an official language in Morocco,

in addition to Arabic. Over 80% of the population of Morocco has

Tamazigh ancestry, but their language was not recognized until recently.

New possibilities are growing as the diversity of the country is

embraced.

Naoual

and her friend then took me on a small tour of the gardens behind the

town. She showed me the water source, where Anzal’s water is filtered in

from a nearby spring. The water descends from the spring into two

divergent paths, towards the reservoir, or off towards the village.

Trees line the cement channel made for the water. Twinkling olive trees

baked in the sunlight, and shriveled pomegranates littered the ground

with their seeds. The gentle breeze flowed through the valley, as if it

had come from far off mountains, and the eternity of ground and sky. We

talked about our lives, the differences and similarities, hopes and

possibilities. As the sun began to set, we made our way back to the

Association.

We left the open valley and returned to the unadorned room with the weavers.

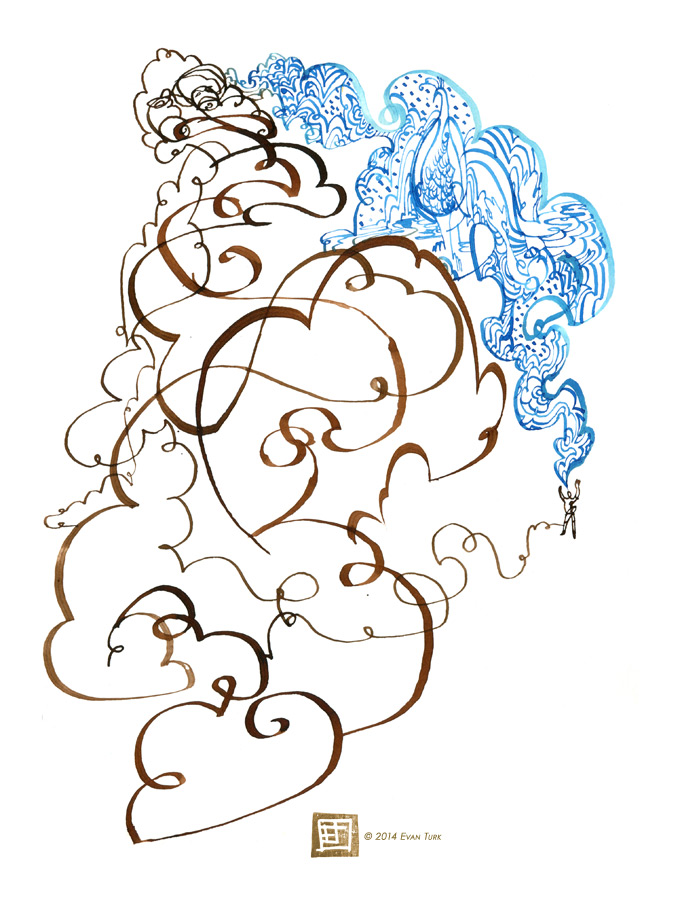

A

new weaver, Fatima, joined them with her carpet stretched on the loom.

Undulating mountainous forms (or are they clouds?) overlap and emerge as

she worked. The pattern grows, creating both ground and sky within the

confines of her warp, but extending in all directions into infinity.

We

then went to her mother’s house where I met her mother, brother, and

sisters as we ate bread, honey, almonds, and ground dates, and laughed

while sipping our hundredth cup of delicious mint tea.

She took me to her aunt’s house where her cousins, aunt, and grandmother were doing household chores and weaving.

Her

grandmother, with high, bronze cheeks and a warm smile, cracked almonds

from their trees out of their shells with a stone in the back. She

laughed as she saw her portrait, saying she couldn’t wait to tell her

son that today she met a man from America who said she looked like his

own grandmother.

The

act of weaving is often related to that of speech, or storytelling. A

tale is referred to as a “good yarn” and stories are “woven” in twists

and turns. The words "text" and "textile" even come from the same Latin

root,

texare, which means "weaving." The looms serve as

repositories for words and thoughts not necessarily spoken. Patterns and

symbols come together across the landscapes of the carpets, often with

stories of pregnancies, births, deaths, and weddings. Like scrapbooks,

created over months, the knots are woven in time as life events unfold.

Older carpets seem to have been formed organically, with no plan in

mind. There is just the warp to hold it together, and life to fill in

the spaces as it comes.

In the ebb and flow,

In warp and weft,

Cradle and grave,

An eternal sea,

A changing patchwork,

A glowing life,

At the whirring loom of Time I weave

The living clothes of the deity.