While in the city of Fes, we had the wonderful opportunity to tour and draw at the Moroccan architectural decoration workshop of

Arabesque (Moresque). While at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, I noticed the brand name in the videos of the construction of the new, very beautiful

Moroccan court in their Islamic Art wing. I contacted Arabesque, the creators of the court, and they welcomed us to come and draw in their workshop for a day.

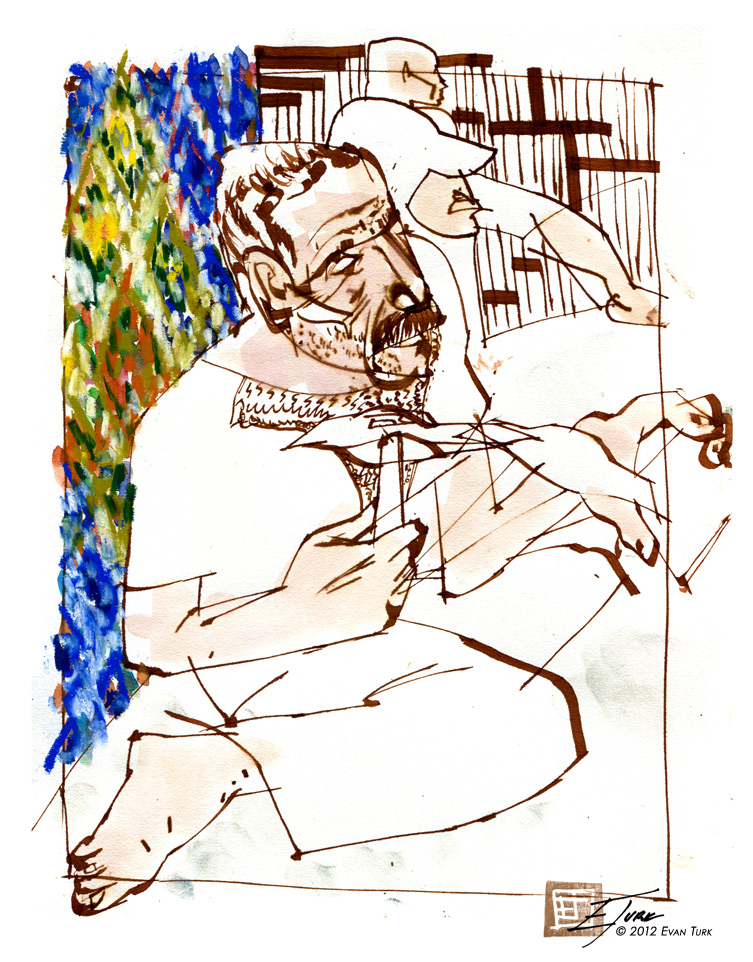

The factory was in the Ville Nouvelle, the modern city outside the medieval medina. It was a sprawling three floor establishment, with the dozen or so zellij tile workers huddled together in one small dusty corner on the first floor.

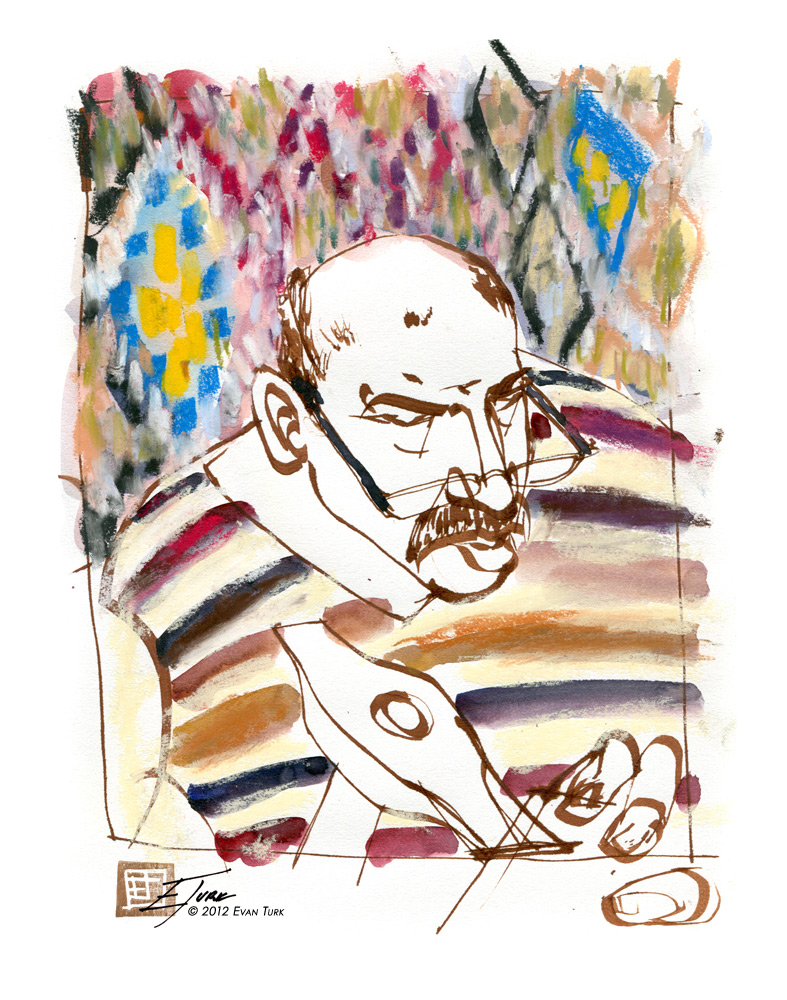

The other floors housed incredible in-progress display rooms that were created using modern designs and techniques as well as replicating each individual period of Islamic decoration with perfect attention to detail. The colors, glazes, patterns, and shapes were created using the original period-specific methods. The detail, precision, and beauty were incredible to see. All of the carved plaster, stained glass, intricately painted wood, and zellij tile were all created by the master craftsmen there.

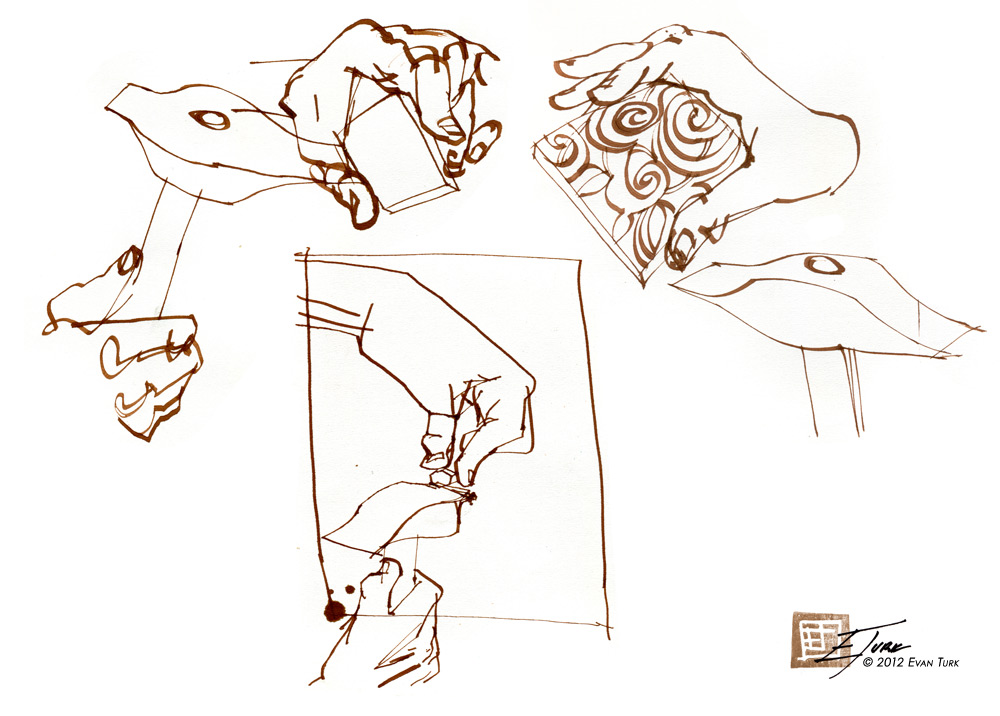

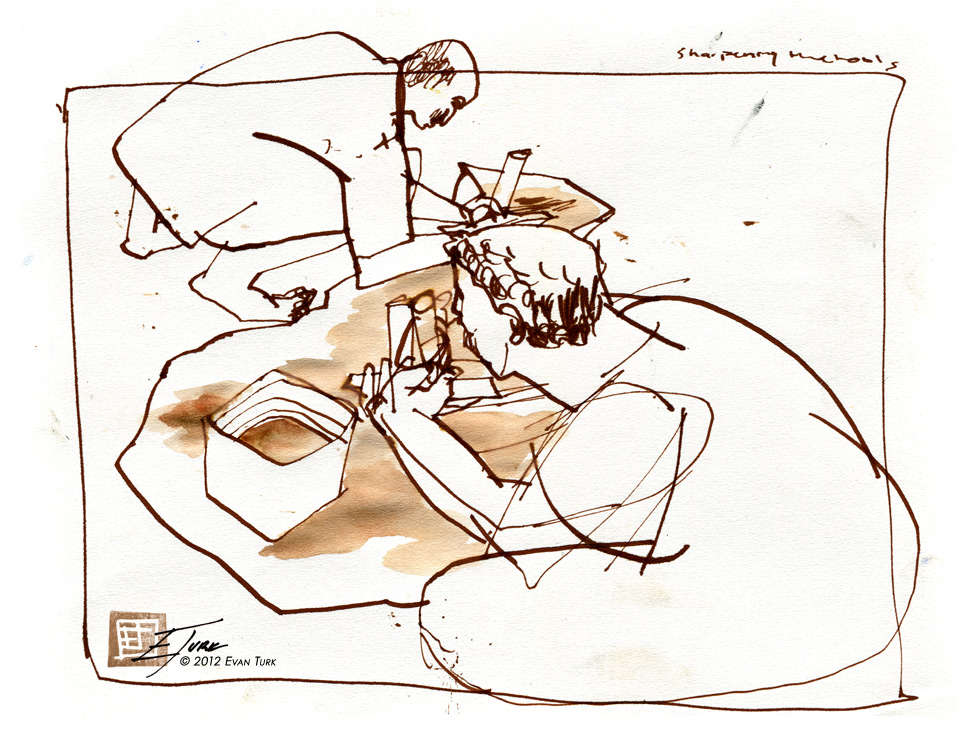

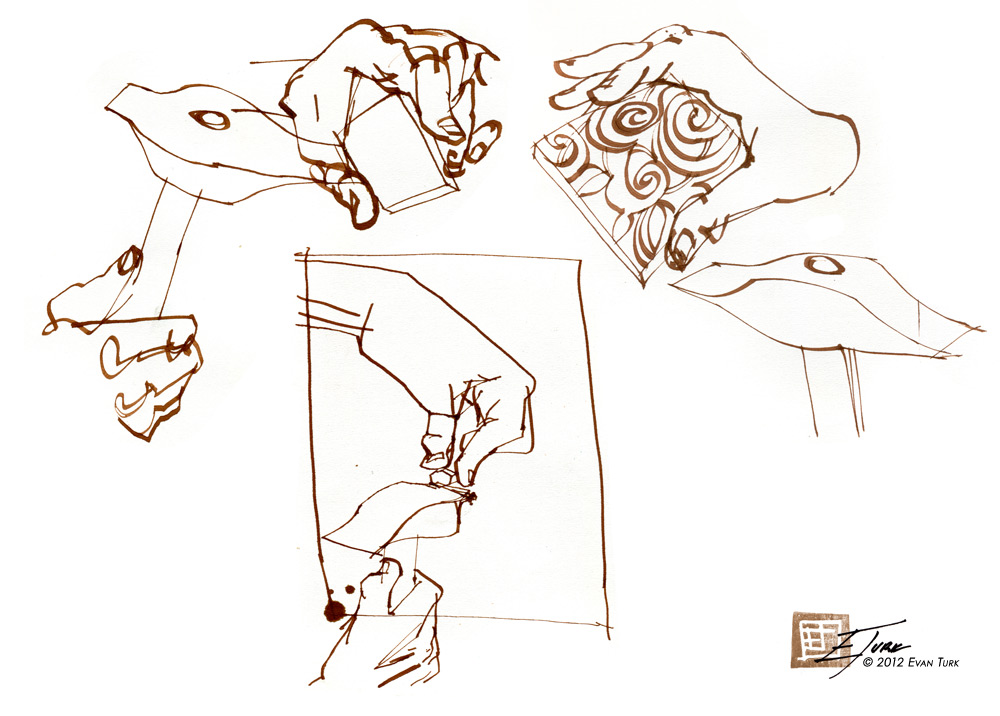

I spent most of my day watching the workers on the first floor, listening to the repetitive tinkling of the chisels on tile. The incredible amount of work involved in creating just one tiny tile is awe-inspiring when you consider the scope of an entire wall. Each shape must be traced out onto the tile in a white paste, and then every extra piece chiseled away to perfection. The glazed ceramic tiles are held against a cinder-block and tapped

precisely and delicately with a surprisingly hefty chisel until it has

been chipped into the specific shape to fit into the overall design.

Each man had a specific task. One would draw the design onto a tile; some would chisel the raw tiles into large squares;

some chiseled the squares into smaller pieces;

some chiseled them into even more intricate pieces;

some stopped to sharpen their chisels;

some stenciled designs on tiles and chiseled away scrolling pieces of a larger pattern;

and all together they worked like pieces of a machine to create beautiful, mind-boggling work.

It was a wonderful experience to be able to spend the day there, and to see the whole process. Many thanks to Adil M. Naji, the President and CEO of Moresque/Arabesque, for agreeing to have us come and for his wonderful hospitality, and to all of the craftsmen for their warmth, kindness and willingness to let me impose on their work.