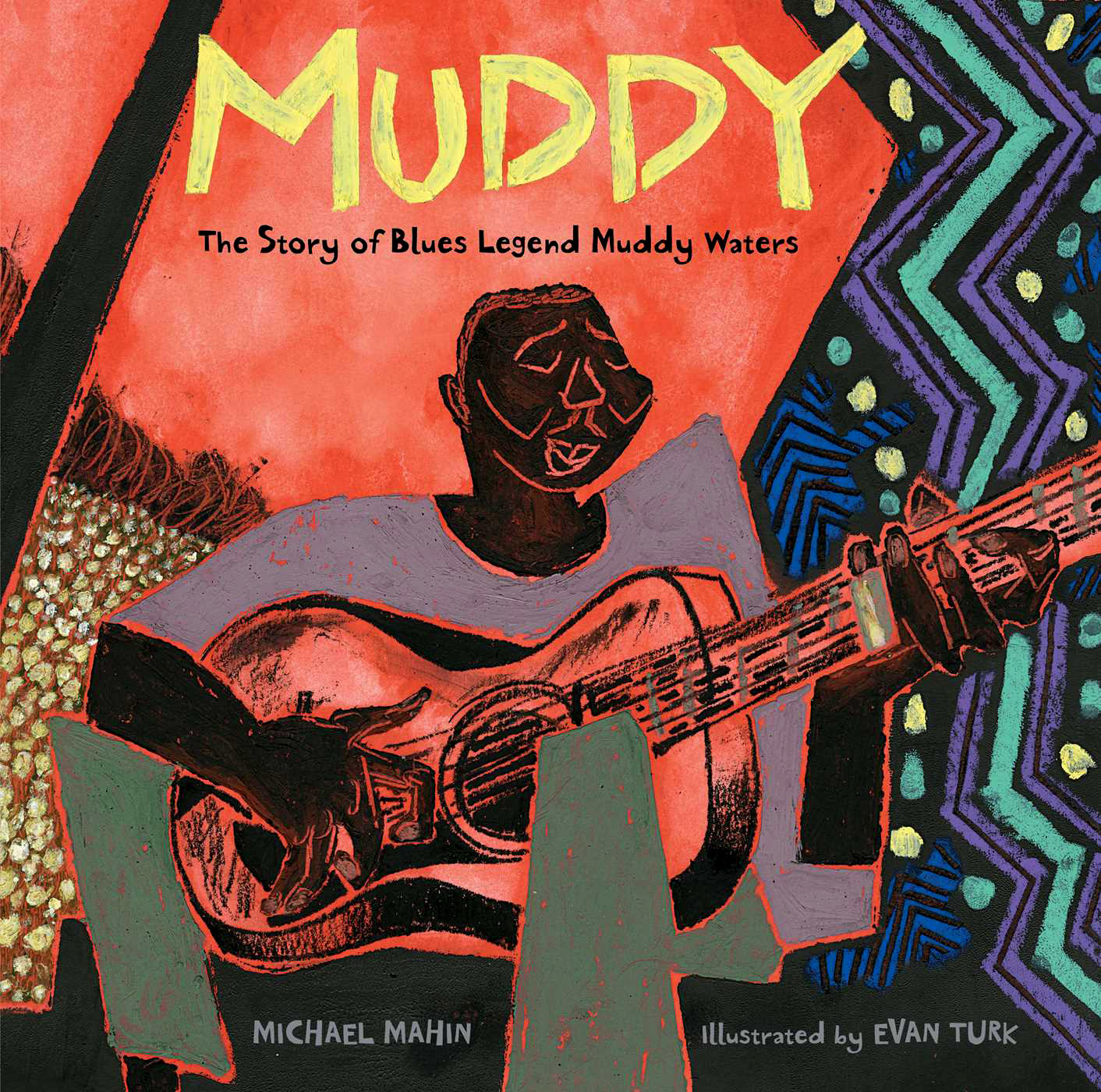

I'm so excited about the upcoming release of the next book I worked on, Muddy: The Story of Blues Legend Muddy Waters, written by Michael Mahin! It won't be available until September 5, but here's a sneak preview and a little "behind the scenes" about the creation of the art for the book.

|

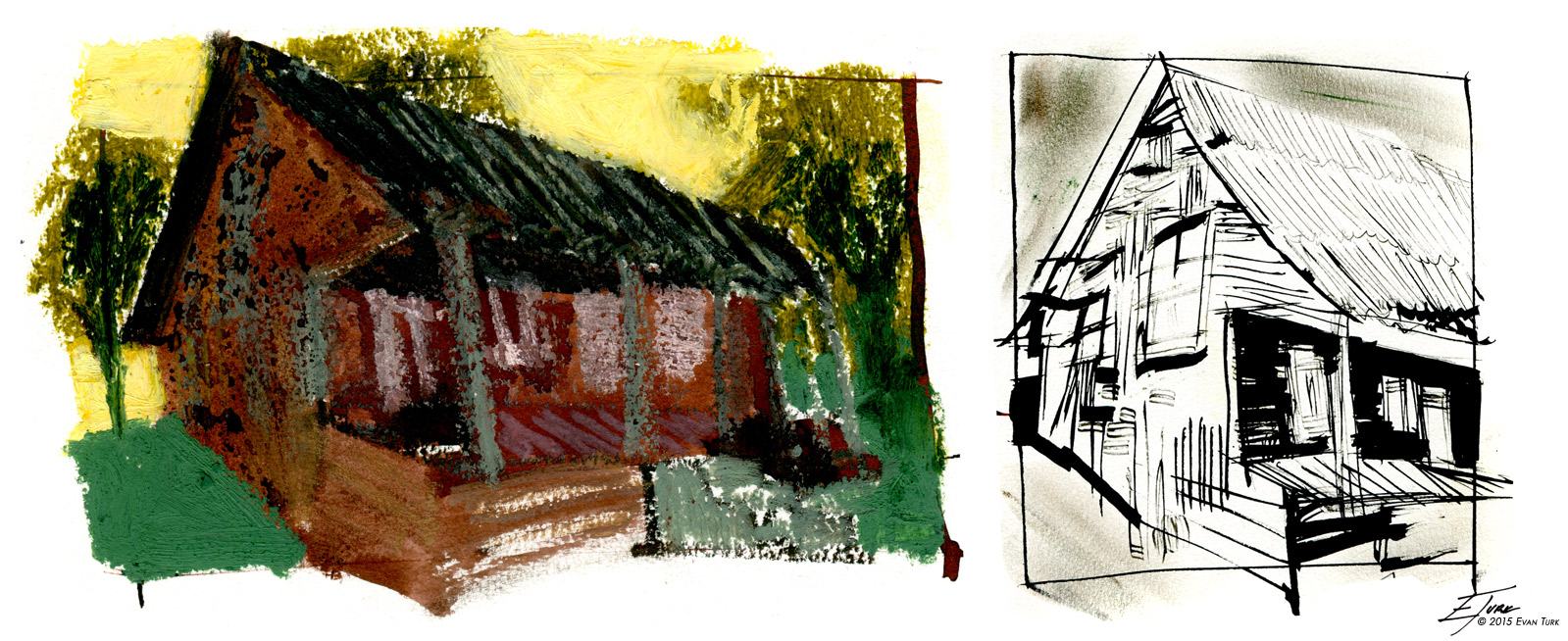

| Research drawing from Clarksdale, Mississippi |

With every new book comes a new research process! You can read more about the research for this book in two blog posts I wrote last year about my trips to the Mississippi Delta, where Muddy was born, and Chicago, where Muddy created his signature sound.

|

| Research drawing from Chicago |

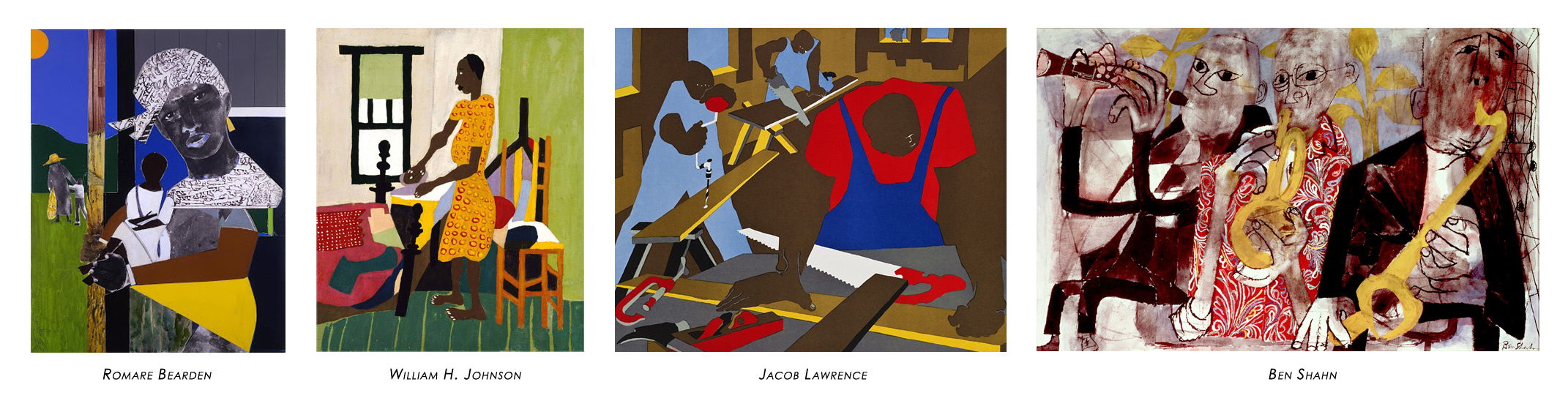

Another part of my research is always to look at artwork to help create a visual style and language that is specific to the topic and the story. Whenever I do school visits (more info here), I like to talk to kids about this step. I hope that it will inspire them to take a look at artists and art they may not have known before.

For this project, I was very excited to get to take a deeper look at some of my favorite artists, including Ben Shahn, Matisse, Picasso, and particularly Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and William H. Johnson.

I also looked at quilts by the Gee's Bend Quiltmakers of Alabama, a group of African American women who have been creating unique, varied, and innovative quilts for decades and generations. Many artists of the Harlem Renaissance (including Lawrence, Bearden, and Johnson) looked to the African American quilt-making tradition and African art for study and inspiration, as well as contemporary European art movements.

The incredible composition and rhythm of their quilts inspired the design for the artwork in Muddy. If you look at the small color thumbnail pagination I made while planning the book (below), you can see the influence of the blocks of color of the Gee's Bend artists.

|

| Color pagination of thumbnails for Muddy |

I wanted the illustrations to show the journey of Muddy and his music from his roots in Mississippi, the electric explosion in Chicago, and his synthesis of the two. I showed this in a few ways:

One was in the newspaper collage. In sharecropper cabins, like the one Muddy grew up in in Clarksdale, Mississippi, they only had newspaper to wallpaper their walls. So I collaged newspapers from the local Clarksdale Daily Register from 1918 on the walls.

|

| In progress collage |

You can see what it looked like here before I painted on top of them. Here the headlines are mostly about small town things like the cost of cotton or stories about World War I.

When Muddy moves to Chicago, he is surrounded by the headlines of the Chicago Defender, a legendary black newspaper. Here the headlines are about African American triumph and struggle, and civil rights issues of the day. And once Muddy becomes famous, he finds himself among the headlines of African American heroes in the Chicago Defender.

|

| Preliminary sketches for Muddy |

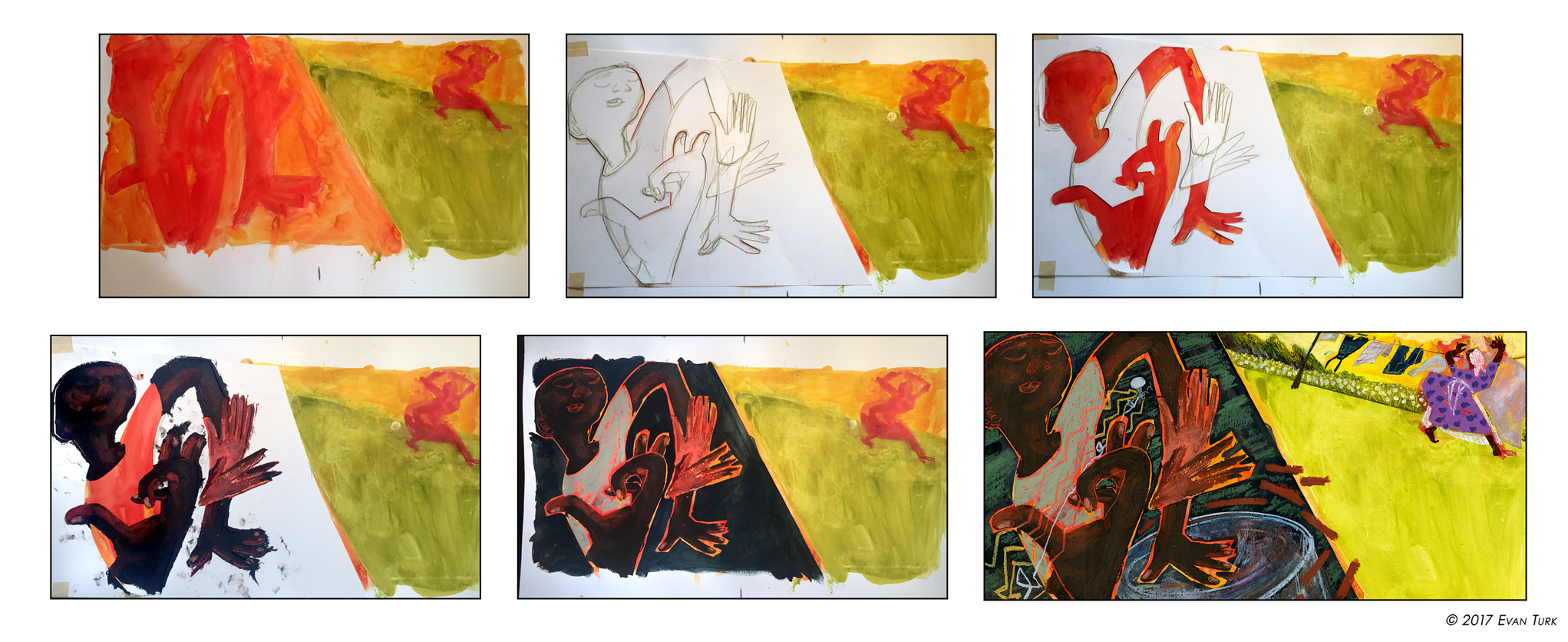

I also used color and a style shift to signify Muddy's journey.

|

| Final art scenes from Muddy in Mississippi |

|

| Final art scenes from Muddy in Chicago |

But when he arrives in Chicago, he is surrounded by the clashing neon colors of the city. The green is no longer earthy, but slick and electric. The blue is not deep and powerful, but bright, cool, and modern. The bright red halo of Muddy's country roots makes him stand out among the city slickers.

But once Muddy begins to let his true self out in his music, everything begins to come together. There is the electricity and intensity of the city, but also the richness, and depth of the Mississippi River, the cotton fields, and the memory of his grandmother. Everything pieced together like a quilt.

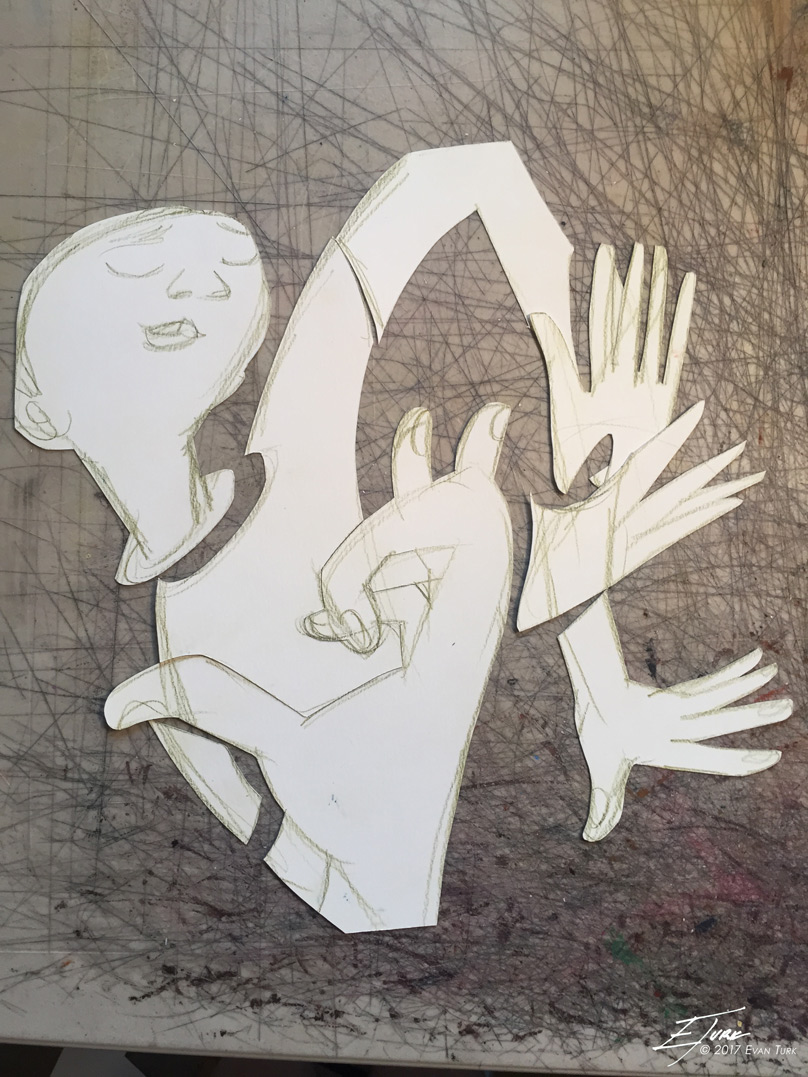

The illustrations themselves were pieced together like a quilt as well.

I drew out the composition, and then cut out each of the shapes to make

stencils. Then I filled in the shapes thickly with oil pastel on top of a

watercolor/gouache background.

Then details and patterns were created by

adding more oil pastel, or scraping it away with a palette knife to make

textures and different effects.

|

| Muddy learning the bottleneck slide from his hero, Son House |

The whole progression of art throughout the book was to show how Muddy grew and changed with his music, but also how he always stayed true to himself.

Muddy: The Story of Blues Legend Muddy Waters will be released on September 5, 2017.

More information and pre-order links here: